Chapter 2

Sharpened by Promise and Adversity, 1928-1948

by Henry K. Sharp, Ph.D.

*edited for online viewing, see book for full text

The morning of Tuesday, 22 October 1929, dawned cloudy and cool, with rain on the horizon. Bronze and yellow leaves fell from the Biltmore ashes by the East Range and beyond the long walk leading up to the Rotunda—by all appearances an ordinary damp autumnal day. Yet the season was not ordinary, either for the University or the nation. That morning the chairman of the Medical Society of Virginia called to order the first session of a three-day meeting held at the University. In attendance were UVa President Edwin A. Alderman, U.S. Surgeon General Hugh S. Cumming, the Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur, and various other distinguished guests, alumni, faculty, and students.

The gathering was a congregation of dark overcoats and black umbrellas, shaken out onto the marble paving stones of a polished Ionic portico—the dignified entrance to the University’s brand new facilities for the School of Medicine. Yet, before this dedicatory gathering of pomp and optimism celebrating modern progress drew to a close on October 25th, the overheated prices of stock certificates traded on Manhattan’s Wall Street had begun a precipitous free fall that propelled the country and the rest of the developed world into an economic depression that would last more than a decade.1The Great Depression left a tragic mark on medicine and health care around the globe. At UVa, the hospital faced increased numbers of poor patients unable to pay for treatment and decreased revenue for services and operations which strained the medical program. Extreme overcrowding of the hospital and outpatient departments led to draconian limitations on admissions, particularly for charity patients, and served to magnify the life-threatening difficulties presented to individuals with chronic, but not emergency, conditions.

Nevertheless, the expenditures which came with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal—however contested that economic philosophy may have been at the time—greatly benefited the hospital. Those federal grants brought to fruition each one of the three much-needed expansions of the University’s medical complex planned in the 1930s and executed with growing intensity after World War II.2 Not merely an issue of greater space, these facilities enabled the University to fund the critical medical and scientific research which has brought nearly three generations of remarkable innovation to medical practice. Although economics and medicine have been intertwined throughout history, with increasing measure through the twentieth century the two have become as tightly bound as the twin serpents on the caduceus, ancient symbol of the profession.

After the series of improvements made to the University’s medical curriculum which Paul Barringer and Richard Whitehead spearheaded—including lengthening the years of study required for a medical degree, integrating clinical experience, raising admissions standards, and an emphasis on research—the fortuitous completion of the new medical school before the economic crash made available a capacious and much more functional facility for teaching, research, and treatment at the precise moment when these needs would be most keenly felt. Before 1929, medical students and faculty had been scattered around the University grounds. Medical students and faculty trudged between the Hotels of the East Range to laboratories and lecture halls across the Lawn at the north end of the West Range and to Jefferson’s old Anatomical Hall, as well as further west to the chemical laboratory and to the small anatomy buildings descending the slope on the far side of the ridge. The new building united all these various facilities into one well-coordinated, centralized structure attached to the existing hospital. Moreover, concurrent renovations to the hospital yielded enlarged facilities for X-ray therapy and diagnosis, a new suite of operating rooms in the place of the administration building’s surgical amphitheater, and an outpatient department tripled in size—effectively a modernization of the medical school’s clinical training capabilities.3

During the 1920s and 1930s that focus rested on the physicians as a proactive factor to limit as much as possible the debilitating effects of all diseases. Consequently, the medical profession promoted regular examinations of healthy individuals to allow for early diagnosis and treatment. In this context, the rationale for the McIntire Wing of the UVa hospital, which Kimball had designed at Hough’s insistence in 1922, becomes clearer. For Hough had asserted that, “Disease must be detected in its incipiency.”4 Although obstetrics, pediatrics, and orthopedics were independently developing specialties, Hough united all in one facility to provide primarily pre- and post-natal care for children. Physicians would be able to implement the precepts of preventive medicine in the lives of young patients as early as possible and to the limits of its application; in sum, to address the maladies of the child that the adult might live more fully. One could easily discern the fear of polio—the scourge of youth—behind Hough’s actions, though the medical school dean pressed all specialties to engage in preventive medicine as well. Significantly for our story, he confirmed that, “Already the surgeons are instituting active propaganda to enforce the necessity of early recognition and treatment of cancer.”5

On that cool, wet Tuesday in October 1929, University president Alderman stood on the new stone foundations of the medical school to offer a dedicatory address that established the idea of prevention at the very core of the profession. “Medicine always has had and still has for its end, the cause, the nature, the cure and the prevention of disease,” he stated, looking over his characteristic pince-nez to the assembly, but…

It may be claimed for the twentieth century, I think, that the career of medicine pursuing these ends is a new career, the science itself almost a new science in its vast volume of added knowledge and disciplines, its new instruments of precision, its methods of diagnosis, and the modern scientific physician is evolving out of a career of beautiful individualism into a blend of scientific humanist, persuasive crusader, and heroic public servant.6

The president’s remarks did accurately depict the rapidly changing conditions of medical practice. Collaboration was only to become more critical to effective healthcare as time progressed, as pathology, surgery, and roentgenology together formed the diagnostic and therapeutic foundations for contemporary medical care. In particular, the relationship between these three fields was pivotal for cancer which presents across a whole range of specialties.

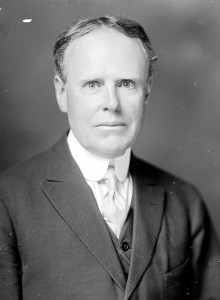

Paul G. McIntire, 1918. Holsinger Studio Collection (MSS 9862). Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

Goodwin and Archer had recommended the ideal institutional response to cancer, and as often transpires, this did not occur immediately or exactly as they intended. The McIntire Tumor Clinc, rather than being a separate, physical, purpose-built space, was a weekly clinical meeting for faculty, housestaff, nurses, and students to coordinate cancer care and to review new and pre-existing cases from both the hospital and outpatient services. Appointments to the clinic’s executive committee balanced the interests of the principal medical services involved in cancer care: surgeons, roentgenology, and pathology.

Although constituting a significant compromise from an independent facility, the McIntire Tumor Clinic contributed substantially to the level of cancer care offered at the University Hospital. Most importantly, the clinic provided an officially sanctioned mechanism for the collaboration of specialists. It also permitted supervision of treatments and organization of patient records for follow-up, an arrangement that encouraged the consultations and analysis which Dean Hough and the New York physicians had urged as essential to effective modern medicine.9 Additionally, McIntire’s donation served to promote professional standards and training.

The disappointingly low numbers of permanent cancer cures—using either surgery or radiation—did show greater promise of improvement as a result of developments in radiotherapy. Most crucial of these advances was the discovery of the fractionation of radiation doses at Madame Curie’s Radium Institute in Paris in the 1920s. Early on researchers observed that the use of single, massive X-ray doses for deep lesions caused permanent damage to the skin and nearby healthy tissues of cancer sufferers. However, Claude Regaud, and later Henri Coutard, determined that breaking the large dose into multiple, smaller exposures proved both more toxic to the malignancy and much less so to the surrounding tissue, which recovered fully from the radiation burns.10 The Parisian experiments attained five-year remissions in over a quarter of cases previously considered hopeless—as far as surgical and radium treatments were concerned—and the deep therapy machine Archer eventually acquired in 1933 enabled him to replicate these results. Scientists at Memorial Hospital worked to apply the fractional methodology to radium, in conjunction with X-rays, and achieved positive results that Archer was able to attain at Virginia as well.11 Thus, through radiotherapy, UVa was at the national forefront of cancer treatment for the first time.

One of Archer’s guiding principles in undertaking radiotherapy was the absolute certainty that malignancy, unchecked, would kill the patient. The side effects of radiation with modern methods were well worth the therapeutic results, even if a very small percentage of cases still developed protracted burns or succumbed to the disease. He cautioned physicians, “Do not forget that the disease is 100 percent fatal, the treatment a fraction of this… [so where there is] a possibility of cure, we are justified in normal tissue damage, which in by far the majority of instances is not permanent.”12

By 1940 Archer and Fletcher D. Woodward, a University of Virginia otolaryngologist, had reviewed the cases of a number of patients who had been seen for various otolaryngological malignancies in the Tumor Clinic and remission then became the issue. Results varied, but even in cases where survival was relatively brief, Woodward and Fletcher concluded that their evidence demonstrated that the outcomes, on the whole, were promising. For these men on the front lines of what the profession considered an epic battle, periods of survival extending beyond that of the standard prognosis demonstrated a significant move towards victory. It would be the task of a later generation to consider questions bearing on the quality of that lengthened life.

Seven years after the establishment of the McIntire Tumor Clinic, when Archer and Woodward wrote their review, it functioned essentially as anticipated. The committee guided the therapeutic decisions of physicians and provided a means to catalogue reactions to treatment in a clear, evidentiary manner. At this time, the clinic meetings reviewed fifteen to twenty patients per week in meetings, and maintained files on 2,200 cases.13 Archer and Woodward resolved that, “In spite of the crude weapons at our disposal today, the treatment of malignant tumors is by no means hopeless and with adequate State support and constant education of the physician and public, even better results should be obtained year by year.” 14 Previously in 1907, when the Rockingham farmer ventured to the University Hospital for a sarcoma of the lower jaw, he underwent two surgeries performed by Stephen Watts, perhaps watched by medical and nursing students leaning out from the rising tiers of benches in the amphitheater. Later Watts and his students would have come to the patient’s bed on ward rounds before discharging him when the surgical incision healed. Had the same man presented to the hospital thirty years later, his ward bed assignment may have looked familiar, but his overall experience of care would have been vastly different and not merely because of technological advancements. A team of physicians and nurses would have examined him in the tumor clinic: first to determine the best course of treatment, a second time to review the progress of his immediate convalescence, and at least a third time to analyze the course of his condition in relation to other cases on record. One could guess that Edwin P. Lehman, Goodwin’s successor as head of the clinic, might well have concluded that surgery was still indicated for the farmer, but Lehman would not have reached that conclusion alone, as Watts had, but in consultation with other members of the surgical and medical departments. Treatment discussions often included Woodward, the specialist in ear, nose, and throat diseases; Archer, specialist in radiotherapy; Cash, expert in pathological analysis; as well as nursing specialists, such as Thelma Holt; and the respective residents and interns. A whole team of individuals then was able to bring complementary areas of expertise to bear on treatment and follow-up decisions at UVa, quite a dramatic change over a generation. In recognition of the positive potential of this kind of collaborative care, the Cancer Committee of the Medical Society of Virginia certified the hospital’s cancer program in 1940 along with five others in the state.15

Access to quality care had long presented a problem in medicine—not simply during the Great Depression—but it was during this period that the increasingly institutional structure of care began to crack under stress. Financial restraints negatively impacted the care of all patients, but the necessity of collaborative treatment for those with cancer made those individuals more vulnerable to the consequences of cutbacks within the hospital. Hospital Director Carlisle S. Lentz maintained a waiting list for prospective patients that numbered into the multiple hundreds. In 1933, he stated, “[W]e have had to assume the attitude that practically nothing but emergency cases be admitted,” readily conceding that:

There have been a number of early malignancy cases which have had to be refused for similar reasons. In cases of this type every minute counts and undoubtedly many will ultimately pay with their lives because of the delay caused now… because the patient with early symptoms does not have the urgent appeal which the broken leg causes and acute surgical cases present. Consequently our admirable facilities for early diagnosis in the Departments of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics have in a great many instances gone begging.16

The executive committee of medical faculty in charge of hospital operations discussed with hospital administration the application of the term ‘emergency’ as a mechanism to override admission restrictions in place for individuals unable to pay. “I have always thought that early cancer should be declared an emergency and the patients admitted immediately regardless of their financial status,” roentgenologist George Cooper stated, in response to several denied admissions.

The fact that patients were not diagnosed or were denied early care as a result of reduced access to physicians contributed heavily to dire treatment outcomes for cancer. This situation was even more dismal for Americans who continued to struggle financially. There needed to be additional points of access for lower-income patients to receive medical screening and care. It was thought that then the total rates for cancer remission and cure would improve. To this end the Albemarle County Home Demonstration Club, a women’s charitable organization, and the Albemarle County Medical Society—in conjunction with the University Hospital, the American Cancer Society, and the local Community Chest (a forerunner of the United Way)—established the Bessie Dunn Miller Clinic for Cancer Prevention in early 1945. The clinic operated out of a room in the University Medical School, with the object of providing routine annual or semi-annual physical examinations to individuals without obvious medical conditions.

On a national level, the disappointing numbers on remission motivated the Roosevelt-era Congress to mobilize federal resources to investigate “the cause, prevention, and methods of diagnosis and treatment of cancer.”17 This was to be achieved through the creation of a new federal institute dedicated to cancer in 1937: the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Congress intended the NCI to be not only a center of research, but also a source of financial and intellectual support for other institutions researching the disease, primarily through grants.

Following post-World War II trends in both clinical care and medical education, UVa’s expanding interest in cancer research was integrated into its medical curriculum. The same year as the University received its first research grant for cancer, 1946, W. Gayle Crutchfield’s neurosurgery department offered an elective course for medical students: Diagnosis and Treatment of Brain Tumors. Two years later, McIntire Tumor Clinic director William H. Parker taught another elective course, The Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer. Surgery, urology, and pathology faculty all published papers on cancer topics at this time.18 In the 1949 academic year H. Rowland Pearsall, an internist, began to offer additional cancer courses, formalized in 1950 with the establishment of oncology as a course subject in the medical school curriculum.19 Thus, by the late 1940s, faculty pressure was mounting for a specialized cancer research and teaching facility.

In 1952, a new multi-story facility linked to the rear of the 1901 administration building opened. The structure contained cancer research laboratories and additional space for the McIntire Tumor Clinic meetings, as well as ward and classroom space for other departments.20 This building symbolizes that the University both acknowledged the necessity of addressing cancer specifically and of integrating its research and treatment into the heart of the hospital’s activities. This shift was reinforced when the U. S. Public Health Service offered a cancer education grant to the University—complementing a partial construction grant for the facility—and the medical school brought in a new professor to coordinate the entire cancer program. Vincent P. Hollander, professor of internal medicine, arrived in December 1952, and took charge of the oncology curriculum.21 Cancer research and teaching—and with them, modernization of cancer therapy—had finally come into its own at the University of Virginia.

University Hospital, circa 1941. In the foreground is the newly completed five-story addition. The Barringer Wing, used for private patients, is in the distance. Historical Collections, HSL, UVa.

- Dedication Exercises of the New Buildings of the Department of Medicine of the University of Virginia, 22 October 1929 (Charlottesville: Michie Company, [1929]), 25. The morning session was in Cabell Hall auditorium, and in the afternoon the attendees toured the new medical school building; the academic procession was interrupted by rain. Weather, The Washington Post, 22 October 1929, Sudden Avalanche Wipes Out $3,000,000,000 in Paper Values, and $3,000,000,000 Lost When Stocks Crash, The Washington Post, 24 October 1929, 1 and 16. Sales Record Is Set While Prices Crash, The Washington Post, 25 October 1929, 1. [↩]

- The three major expansion projects planned in the 1930s were the Barringer Wing (1935) for private patients, the Davis Wing (1939) for neuro-psychiatric patients, and the West Addition (1940), which expanded the three original pavilions into a new central building for the hospital. Carlisle S. Lentz to John L. Newcomb, 24 July 1933, Box 16, Department of Medicine 1930-1933, Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries I, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library; Box 13, 1934-1936 Hospital Addition, and J. A. Anderson to John L. Newcomb, 5 December 1934 and Box 17, Medical Department, Hospital Addition, Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries II, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library; Box 7, 1937-1938 Hospital, Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries III, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. [↩]

- “Department of Medicine Occupies New Labs,” UVa Alumni News 17, no. 7 (March 1929): 159; “New Medical Building Is Unsurpassed in Beauty, Convenience and Equipment,” UVa Alumni News 18, no. 2 (October 1929): 30. [↩]

- Ibid [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Dedication Exercises of the New Buildings of the Department of Medicine of the University of Virginia, 22 October 1929 (Charlottesville: Michie Company, [1929]), 29. [↩]

- C. Flippin to J.L. Newcomb, 15 July 1933, Box 16, folder: Department of Medicine, Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries I, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library; Report of the Committee Investigating the Establishment of the Paul Goodloe McIntire Memorial Clinic, 2 May 1933, Box 16, folder: Department of Medicine, Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries I, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library; W. H. Goodwin to J. L. Newcomb, 1 May 1934, Box 17, folder: Department of Medicine, Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries II, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. [↩]

- Report of the Committee Investigating the Establishment of the Paul Goodloe McIntire Memorial Clinic, 2 May 1933, Box 16, folder: Department of Medicine, Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries I, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. [↩]

- Report of the Committee Investigating the Establishment of the Paul Goodloe McIntire Memorial Clinic,” 2 May 1933, Box 16, folder: “Department of Medicine,” Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries I, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. [↩]

- Henri Coutard, Principles of X-Ray Therapy of Malignant Diseases, Lancet 227 (7 July 1934): 1-8. [↩]

- Vincent W. Archer and Walter L. Kilby, “Present-Day Treatment of Certain Malignant Diseases,” Virginia Medical Monthly 62, no. 12 (March 1936): 691-692. [↩]

- Ibid., 692-693. [↩]

- Report of Meeting of the Medical Alumni Committee, April, 1940, Box 1:30, 32, The Papers of the University of Virginia Medical Alumni Association, 1939-1975, CMHSL. [↩]

- Fletcher D. Woodward and Vincent W. Archer, “The Results of Treatment of Malignant Tumors of the Larynx, Hypopharynx, Nasopharynx, and Sinuses,” Virginia Medical Monthly 67, no. 12 (December 1940): 755. [↩]

- Virginia Cancer Foundation Report of Activities (1947): 4. [↩]

- Carlisle S. Lentz to John L. Newcomb, 24 July 1933, Box 16, Department of Medicine, 1930-1933, Papers of the President, Accession # RG-2/1/2.491 subseries I, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. [↩]

- National Cancer Act of 1937, Public Law 244, 75th Cong., 1st sess. (5 August 1937). [↩]

- All the following reports are part of the Annual Reports to the President, 1904-1958, Accession # RG-2/1/1.381, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library: Biochemical Laboratory, 1948, 1949; Anatomy Department, 1949 and 1950; Department of Medicine, 1947; Neurosurgery Department, 1947; Department of Surgery, 1947 and 1949; Urology Department, 1947; Pathology Department, 1948; Internal Medicine Department, 1949. [↩]

- “Detailed Notes Taken at Meeting—May 15, 1948,” section VIII and report 13, Box 2:5, The Papers of the University of Virginia Medical Alumni Association, 1939-1975, CMHSL; UVa Record 36, no. 6 (March 1950): 54. [↩]

- Department of Medicine, 1950 and 1952, Hospital, 1950, Annual Reports to the President, 1904-1958, Accession # RG-2/1/1.381, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. [↩]

- William H. Parker, “The University of Virginia Development Fund, Report of the Medical School and Hospital, 1948,” 14 May 1948, Box 2:10, The Papers of the University of Virginia Medical Alumni Association, 1939-1975, CMHSL; Department of Medicine, 1953, Annual Reports to the President, 1904-1958, Accession # RG-2/1/1.381, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. [↩]