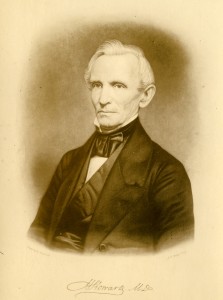

Henry Howard, Photograph of an engraving by A.B. Walter. Courtesy of University of Virginia Visual History Collection (prints16157). Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

Henry Howard was born in 1791 in Maryland and graduated with a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He practiced medicine for 24 years in Montgomery County, Maryland, and taught obstetrics at the University of Maryland for two years prior to joining the University of Virginia faculty in 1839 where he taught Medicine, Physiology, Obstetrics, and Medical Jurisprudence.1

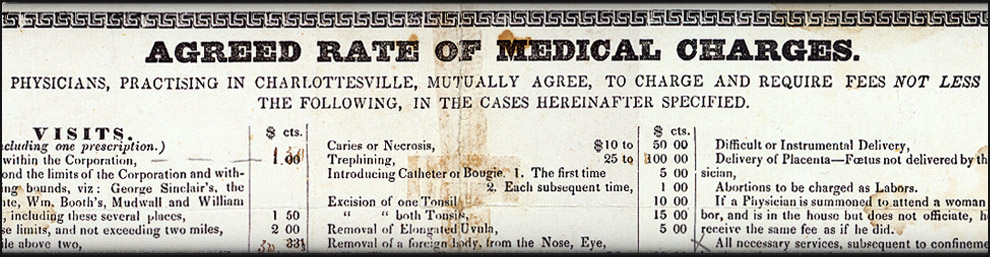

He had two daughters with his first wife, Hannah, and two more with his second wife, Eliza, who died in 1841. At the time of the 1850 census he was living with his three youngest daughters and owned three slaves. He was the oldest signer of the fee bill at age 57. Within several years of the printing of the bill he gave up his medical practice and focused only on teaching.2

Dr. Howard did not play as large a role as Drs. Davis or Cabell during the Civil War, but his name is mentioned as caring for a prisoner of war.3 He retired from teaching in 1867 when he assumed the position of president of the Citizens’ National Bank.4 Shortly after the end of his last session at the University the Charlottesville Chronicle stated, “This community never had any citizen more universally esteemed and respected.” Upon his resignation, resolutions were adopted by the faculty esteeming “his faithful services to the University through alternate periods of depression and prosperity.”5 During the entire Civil War, certainly the time of deepest depression, he missed only two faculty meetings.6 In the 1870 census his profession was listed as banker, and he had the considerable sum of $82,000 in personal worth.7 He was elected to the vestry at Christ Church in 1872 and died in 1874 in Charlottesville.8

- Wyndham Bolling Blanton, Medicine in Virginia in the Nineteenth Century (Richmond: Garrett & Massie, 1933), 26; University of Virginia, Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia (1839-1840). [↩]

- Eugene Fauntleroy Cordell, The Medical Annals of Maryland, 1799-1899 (Baltimore: Press of Williams & Wilkins Company, 1903), 444; U.S. Census: Albemarle, Virginia, 1850, accessed 23 March 2011; Slave Schedule, 1850, Federal Census, Albemarle, Virginia (Charlottesville), accessed 23 March 2011; David M.R. Culbreth, The University of Virginia; Memories of Her Student-life and Professors (UVa Text Collection, 1908), 276, accessed 29 March 2011. [↩]

- Chalmers L. Gemmill, “The Charlottesville General Hospital 1861-1865,” The Magazine of Albemarle County History 22 (1963-1964): 115. [↩]

- Edgar Woods, Albemarle County in Virginia (Bridgewater, Va.: C.J. Carrier Co., [1956?]), 109. [↩]

- Philip Alexander Bruce, History of the University of Virginia, 1819-1919; The Lengthened Shadow of One Man, vol. 2 (New York: Macmillan, 1920), 175. [↩]

- Philip Alexander Bruce, History of the University of Virginia, 1819-1919; The Lengthened Shadow of One Man, vol. 3 (New York: Macmillan, 1921), 316. [↩]

- U.S. Census: Albemarle, Virginia, 1870. [↩]

- Jennie Thornley Grayson, “Old Christ Church, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1826-1895,”Papers of the Albemarle County Historical Society 8 (1947-1948): 53; Woods, 406; Culbreth, 276. [↩]