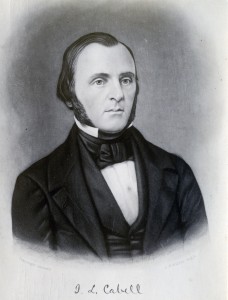

J.L. Cabell. Courtesy of University of Virginia Visual History Collection (prints16145). Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

James Lawrence Cabell, the son of a physician, was born August 26, 1813, in Nelson County, Virginia. After attending private schools in Richmond he entered the University of Virginia in 1829 where he studied Ancient Languages, Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, Medicine, Anatomy & Surgery, and Moral Philosophy, earning his A.M. in 1833. He continued his study of medicine at the University of Maryland where he obtained his M.D. degree in 1834, the same year as James Poindexter.1 Cabell’s medical school thesis was on chronic nervous diseases.2 He then studied in Paris until 1837 when he returned to the University of Virginia as Professor of Anatomy and Surgery. Over the course of more than 50 years of teaching at UVa, he additionally taught physiology and comparative anatomy. He was the most senior faculty member for nearly three decades and the most senior professor in the medical school for over 45 years, continuing to teach through the 1888-1889 session. Not only was he appreciated for his devotion to teaching and his skills as a diagnostician, but also for his zeal for learning in general.3

Dr. Cabell wrote a book titled, The Testimony of Modern Science to the Unity of Mankind; Being a Summary … in Favor of the Specific Unity and Common Origin of All the Varieties of Man. The book advanced the idea of evolution and was entered in the clerk’s office of the District Court for the Southern District of New York in 1858, a year before the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Dr. Cabell’s published papers on medicine were not numerous but excellent in quality. He was receptive to scientific facts and often ahead of the curve in accepting a new paradigm, such as when he recognized the significance of Joseph Lister’s idea of sterile surgery and was willing to promote it when others ridiculed the concept.4

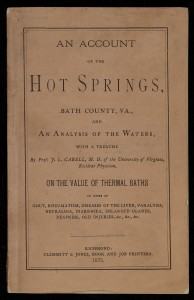

J. L. Cabell, An Account of the Hot Springs, Bath County, Va. Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

In addition to his service to the University of Virginia, during most of the Civil War Dr. Cabell was in charge of the Confederate States Military Hospital in Charlottesville where he demonstrated his administrative abilities. A letter written in July of 1861 states, “There are 1500 patients and two or possibly three commissioned surgeons. Without volunteer aid, by which, owing to their number, the most of the work is done, the case would be desperate. The consequence is that Drs. Davis & Cabell are worked half to death, hundreds of dollars worth of practice is done daily by volunteer physicians, who will never receive a cent therefor I suppose, ….”5 In spite of the overwork the mortality rate over the course of the war was just slightly over five percent, a highly creditable figure given the state of medical knowledge and practice.6

James Lawrence Cabell grave marker. University of Virginia Cemetery and Columbarium, Charlottesville.

Cabell was a resident physician at Hot Springs, now the Homestead, in Bath County, Virginia. He wrote An Account of the Hot Springs, Bath County, Va.: and an Analysis of the Waters, with a Treatise by Prof. J. L. Cabell, M.D. of the University of Virginia, Resident Physician, on the value of thermal baths in cases of gout, rheumatism, diseases of the liver, paralysis, neuralgia, diarrhea, enlarged glands, deafness, old injuries, &c., &c., &c. The treatise was published in 1873 with similar ones biennially from 1869 to 1875. He was part of the Medical Association of Virginia meeting at Rockbridge Alum Springs in 1883 that endorsed the use of mineral water from those springs for people afflicted with various diseases.

A member and organizer of the Medical Society of Virginia, Cabell was elected president in 1876.7 An early agitator for sanitary reform, he helped establish and served as the first president of the National Board of Health which was created by an Act of Congress on March 3, 1879. In that year he was also president of the American Public Health Association and gave an address which was “an exhaustive review of the sanitary situation of the country, and was listened to with marked attention.”8

Cabell married Margaret Gibbons in 1839. He had no biological children but adopted two nieces. He was elected to the vestry of Christ Church, the first church built in Charlottesville, in 1840, and was treasurer for the Chapel Aid Society of the University of Virginia which worked to raise a fund for the completion of the Chapel at the University.9 He was the owner of five slaves at the time of the 1850 U. S. Census.10 He died August 13, 1889, in Albemarle County, Virginia. Addresses given in his honor after his death described him as a “man in whom there was truly no guile. He had the highest sense of honor, the most tender regard for the sensibilities of others …. He was never weak and vacillating in his opinions, but always expressed them, on proper occasions, with firmness and decision.… But the ennobling feature of his character was his deep and abiding religious faith.”11

- Robley Dunglison, An Address, Delivered to the Graduates in Medicine, at the Annual Commencement of the University of Maryland, On Wednesday, March 19th, 1834, Baltimore: William Wooddy, 1834, 23. [↩]

- Robley Dunglison, An Address, Delivered to the Graduates in Medicine, at the Annual Commencement of the University of Maryland, On Wednesday, March 19th, 1834, Baltimore: William Wooddy, 1834, 23. [↩]

- Howard A. Kelly, American Medical Biographies (Baltimore: Norman, Remington Co., 1920), 185; University of Virginia, Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Virginia (1829-30 – 1888-89). [↩]

- Addresses Commemorative of James L. Cabell, Delivered at the University of Virginia, July 1st, 1890 (Charlottesville, Va.: Chronicle and C.M. Brand, Steam Book and Job Printers, 1890), 22-23. [↩]

- Chalmers L. Gemmill, “The Charlottesville General Hospital 1861-1865,” The Magazine of Albemarle County History 22 (1963-1964): 114. [↩]

- James O. Breeden, “Insights into the Medical Statistics of the Charlottesville General Hospital, 1861-1865,” The Magazine of Albemarle County History 30 (1972): 49. [↩]

- Howard A. Kelly, American Medical Biographies, 185. [↩]

- “Discussing Public Health,” The New York Times, November 19, 1879. [↩]

- Jennie Thornley Grayson, “Old Christ Church, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1826-1895,”Papers of the Albemarle County Historical Society 8 (1947-1948): 53; K. Edward Lay, The Architecture of Jefferson Country, Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2000), 160; Chapel Aid Society of the University of Virginia, University Chapel ([Charlottesville, Va.: Chapel Aid Society of the University of Virginia, ca. 1885]), Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. [↩]

- Slave Schedule, 1850, Federal Census, Albemarle, Virginia (Charlottesville), accessed 23 March 2011. [↩]

- Addresses, 40. [↩]